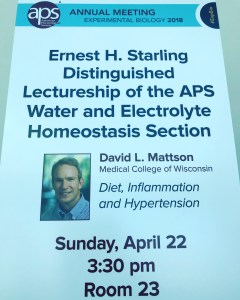

On Sunday David Mattson presented the Starling Distinguished Lecture of the American Physiological Society Water and Electrolyte Homeostasis Section. His talk addressed the role of inflammation in salt-sensitive hypertension, using the Dahl salt-sensitive rat and some supporting human data.

On Sunday David Mattson presented the Starling Distinguished Lecture of the American Physiological Society Water and Electrolyte Homeostasis Section. His talk addressed the role of inflammation in salt-sensitive hypertension, using the Dahl salt-sensitive rat and some supporting human data.

About half of human adults have hypertension, and about half of those patients are salt-sensitive like this rat. Feeding this rodent a high salt diet leads to rising blood pressure and albuminuria, with enlarged glomeruli, tubular damage, and inflammation. Other types of rats given the same level of sodium intake do not develop these findings. Studies from people with hypertension also show increased lymphocytes in their kidneys, suggesting that there are parallels with human disease.

In a series of experiments, Dr. Mattson showed that there were increased B and T cells in these rat kidneys and that the immune cells were activated and producing a number of cytokines. Inhibiting the presence and activity of these immune cells attenuated both the hypertensive and renal damages induced by salt loading. They then took genes identified in human association studies of hypertension and mutated the analogous genes in rats. They transplanted bone marrow from these mutant animals into Dahl rats without the mutation, so only hematopoietic cells carried the mutation in question. When salt loaded, these rats showed less hypertension than intact Dahl rats, suggesting that the immune response provided major input for hypertension.

What about the role of hypertension beating up on these kidneys? Dahl rats have poor autoregulation, so systemic hypertension gets transmitted to the kidneys. They placed an aortic cuff just above the left renal artery in rats and used it to maintain a normal blood pressure into that kidney. The right kidney saw and felt the higher pressure. This maneuver alleviated the inflammatory response in the cuffed kidney.

What about the role of hypertension beating up on these kidneys? Dahl rats have poor autoregulation, so systemic hypertension gets transmitted to the kidneys. They placed an aortic cuff just above the left renal artery in rats and used it to maintain a normal blood pressure into that kidney. The right kidney saw and felt the higher pressure. This maneuver alleviated the inflammatory response in the cuffed kidney.

In the Dahl model of salt-sensitive hypertension, both inflammation and barotrauma appear to contribute to kidney damage. The story does not end here; the Mattson lab is presenting more fascinating work on this topic at this year’s meeting.